Brooke is a biology instructor in the School of Arts and Sciences. Last year, Brooke embarked on a journey she had been looking forward to taking for a long time. “When I was interviewed for my position in 2018, one of my questions to the interviewers was: how does the Biology Department embrace Indigenization? It’s a big part of Camosun College and what this college emphasizes in its identity. Biology has areas that can be easily Indigenized and areas that seem impossible, so when I began teaching, I was just flying by the seat of my pants. I was acknowledging territory, going with students on nature walks, and teaching and learning about SENĆOŦEN names and W̱SÁNEĆ uses, but it was small pieces here and there.” The real beginning of Brooke’s Indigenization journey began with the Indigenizing your Course workshop series she took in the summer of 2022.

“I can’t say enough wonderful things about that workshop. There were ten of us and we all said ‘I want to do this, but I know I’m going to make mistakes. I need to make sure that I’m okay with that and that I’ve been given permission to try.’” As Brooke told me, the program was not about checking the boxes, but about bringing together a community, all trying, failing, succeeding together, and supporting each other in a safe place. “That workshop gave me the confidence, the motivation, and the accountability I needed to move forward.”

One thing that helped Brooke think about how to go about Indigenizing her course was developing a framework. “Thinking about decolonizing your course can be overwhelming and intimidating. Instead, find one thing that resonates with you and start there. For me, my framework was that people are whole. So often we only engage with one part of that whole such as mind and body and I wanted to engage with others such as spirit and emotion.” One thing the workshop facilitators, Natasha Parrish and Charlotte Sheldrake, had Brooke and her workshop colleagues do was write an Indigenization statement, outlining what Indigenization meant to each of them, “[…]because it’s allowed to be different. The statement created accountability and the facilitators made sure that by the end of our workshop, we had our purpose and our framework ready to follow.”

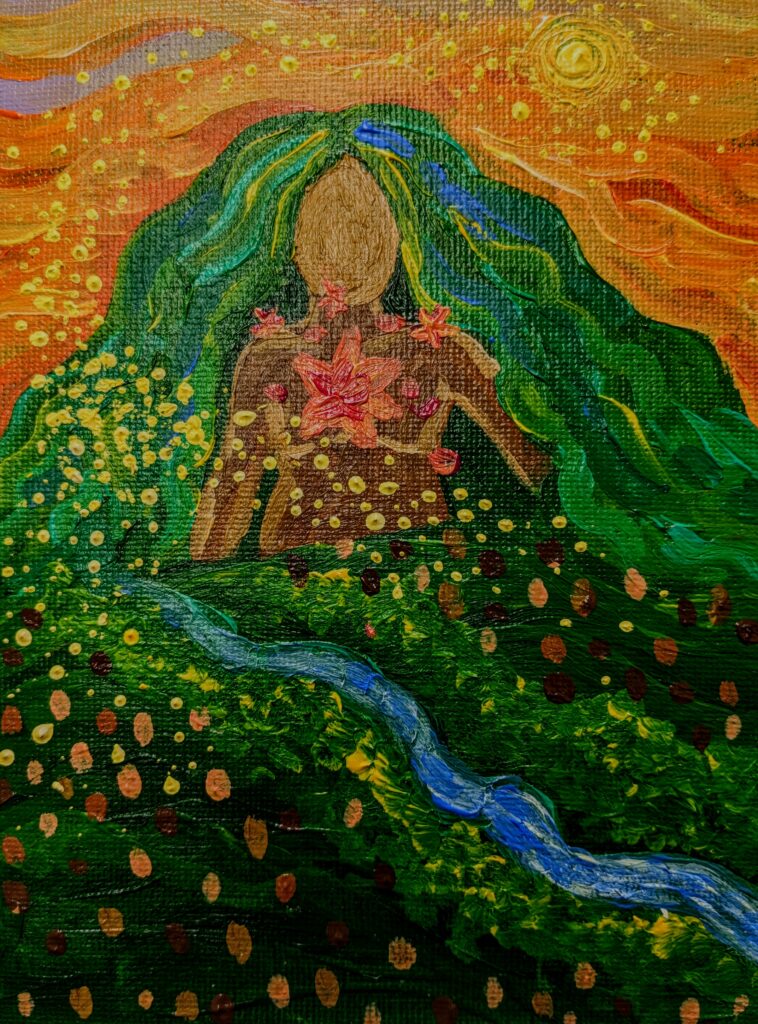

The course Brooke Indigenized was her biodiversity course. “It’s a non-major’s biology course for students who need a science, but who aren’t necessarily going into biology. I thought it was a great course to break down because there was no expectation at the end of the course to entirely focus on the Western science perspective way through and through, so it was a chance for me to open worldviews.” The biodiversity course is a typical science class: lectures, tests, labs, assignments. The first thing Brooke did was remove tests she didn’t think were needed. “What that did was open two lab sessions for something different. I still had my Western science labs – those were still important – but I added a restoration project where we worked with the Saanich district and volunteers at Rithet’s Bog. We learned about the land, engaged in restoration, and connected with the material in a different way. We also took a field trip out to the Salish Sea Centre, where we saw living creatures rather than preserved specimens in jars. We observed how they interacted with one another in their mini ecosystems. I also invited Della Rice-Sylvester, a Cowichan elder and medicine woman, to give us a tour of campus with her eyes.” Brooke and her students were blown away, witnessing another perspective on biodiversity, those spiritual and emotional connections to the land, that had until then been completely absent. Brooke told me that she will be keeping all the changes she made to the labs saying, “I’m only going to be going forward from here.” And when she asked for student feedback, she heard nothing but resounding gratitude for the inclusion of these experiences, saying things like “I needed this in my education, and I didn’t even know I needed it. How could I have gone through my academic career up until now and not have this be part of my learning?” Brooke said, “it was such an easy thing to do and was something I could have done years ago if I had given myself the permission.”

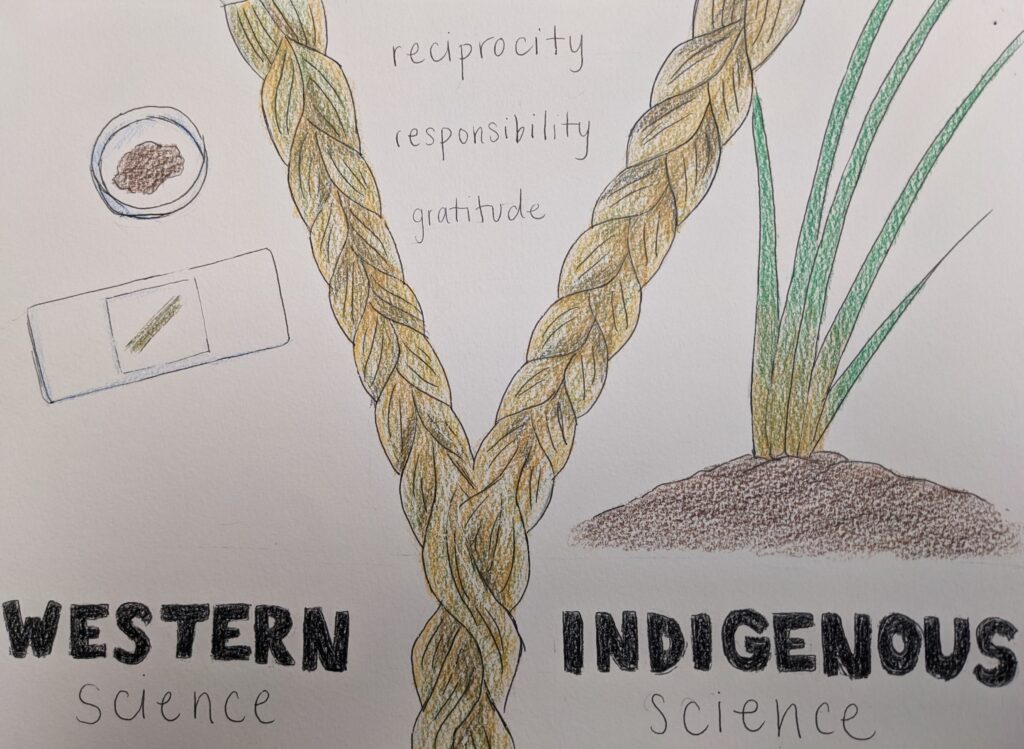

Another aspect of the course Brooke pulled apart was the 20% of the grade from lab exams, putting that grade instead into a book meeting project. “We read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Kimmerer and took five lecture periods, with two or three weeks in between, to meet and discuss the different parts of the book. I provided questions for students to consider, then they came to the book meetings and met in small groups to discuss the book and the questions.” This was Brooke’s chance to encourage her students to express their feelings and their emotions and their spirituality. “We have international students, and students from across Canada, coming in with different perspectives that they could share with the class. You don’t normally see that in a biology course – there isn’t often room for students to make cultural connections.”

In fact, this was the main reason Brooke wanted to Indigenize her course. “Western science is very much focused on ‘what did you see? What is physically there? What did you physically observe?’ And that’s it. But Indigenous science goes beyond that, also looking at how things make you feel and exploring your connection to, and your relationship with, what you observe. What I wanted to do in my course was to give my students an opportunity to discuss their feelings and their connections to what we were observing. And honestly, when it comes to conservation biology, climate change, and the biodiversity crisis, how can you not have feelings about them?”

But how do you assess feelings? “When you’re dealing with emotion and spirit, I don’t think it’s reasonable to assign limits. Sometimes I would see that a student only wrote a sentence, and I would ask them to dig a little bit deeper next time, and the next week they would. They knew that if they read the book and engaged, it was a low-pressure experience for them.” For each book meeting they also had an assignment giving them licence to be creative. “Robin Kimmerer mentions how in Indigenous sciences you see the personhood of non-human life, something not addressed in Western science. One time I asked them to write a story from a non-human perspective: imagine you’re a flower being picked, or a spider trying not to get squashed, or an old growth tree watching as your friends and family get felled. What emotions, what feelings, what knowledge do those organisms have? What is their personhood? But no pressure – I just wanted them to try. And these creative expressions were a gift to read.”

With all these changes, Brooke was not sure how students would react, but she said she had never seen such amazing buy-in. “For the first time since I’ve taught this course, nobody dropped, and nobody failed. I felt so full knowing that my students committed to this journey.” And Brooke clarified that she still lectures and, there were still traditional assessments, but she provided a gateway into Indigenous science. “I was touched to hear my students say, “this education is essential for me; I should be respecting the land; I need to recognize the importance of reciprocity.” These were not concepts I lectured to them. The book taught them, our nature walks taught them, and I provided them space to learn it.” Brooke is keeping the book discussions, but says she may provide more specificity, perhaps through rubrics, because students do like structure and clarity. “Overall, I think my students are at an advantage having these other perspectives and potentially being able to challenge Western perspectives as needed in whatever they study in the future.”

Brooke’s changes also created community, gratitude, and hope as students began to see themselves as part of the ecosystem. “We are such an invasive species and students had a very negative perspective of human impact on the world when they came into the course. But leaving the course, they had hope that we can still recognize our roles and responsibilities and learn to respect our relationship to the land and the organisms on it. They left feeling a bit more empowered knowing that, as humans, we can do better.”

The biodiversity course opened itself well to Indigenization, but Brooke admits that other biology courses are a bit more challenging. “When you’re discussing enzyme pathways in a cell where there’s a molecular change, it’s not necessarily about bringing in Indigenous perspectives on that content, but more about trying to embrace a more holistic view of assessment and course delivery and Indigenous ways of learning.”

Brooke will be sharing her experiences with her colleagues and has already shown them some of her students’ creative projects, but she knows that there will be some questions around how they can Indigenize their courses. “I think that is where the Indigenizing your Course program is important, because the facilitators give you permission to try and to consider: why is it so important that students open their minds to multiple perspectives? Why is that going to benefit our students in their academic career and in their lives? Faculty know that they should, but don’t necessarily know the why or the how, and they don’t often have a community they can try and fail with.”

But Brooke does recognize that in the end, this is a personal journey. “Sometimes being an instructor is exhausting. You have to carve out the space for this work, and that’s a lot to ask. But I don’t want people to be so fearful of getting it wrong that they don’t do anything. It’s okay to get it wrong and to keep trying. Be vulnerable because you are trying something worthwhile. Just commit to one change. And if you think it went well, and if you get good feedback, that might encourage you to do more. You’re not helping anyone when you don’t try.”

Moving forward, Brooke has plans to Indigenize some of her other courses as well as do some more Indigenization work with her biodiversity course. “I’m going to continue to remove content that’s not serving my students and offer Indigenous perspectives. I also brought in three guest lecturers. A fantastic pair of teachers came to talk about climate anxiety and renewable resources speaking from a more social science perspective. An amazing enthusiast came in thrilled to talk about phylum Porifera (sea sponges) and it was great to experience someone’s joy and passion for something most folks overlook. It wasn’t just me as the sole holder of information – this was community-based learning and I’m absolutely going to keep bringing in other voices.” As for her other courses, she is looking at Indigenizing a course that is based on molecular and cellular content, but also about family traits and epigenetics, topics which she thinks will lend themselves to a more holistic approach.

I wanted to close with these words from Brooke, summing up her first Indigenization experience. “I used to think my students just needed to know and do the things I gave them in the syllabus. But now I want to expose them to a variety of perspectives and to engage with the four quadrants of themselves as human beings (physical, spiritual, emotional, and mental). I see them as whole people who deserve to be challenged physically and mentally and to have their emotions and their spirituality addressed – that is what Indigenization has brought to me and my students.”