Brandon began at Camosun 20 years ago, as a student in the same department where he now teaches: Computer Science. “I went out into industry after graduating, was self employed for 20 years, but after the pandemic I had a pivot moment and was given an opportunity to teach here. I wasn’t sure if it would be a great fit, but it turned out that I love teaching. I love mentoring and giving back to the next generation of people in computer science. And now I’ve been here three and a half years.”

I asked Brandon what courses he teaches. “As a generalist, I can teach many of the courses in our programs, but I specialize in web technologies, so typically I teach first-year students in web fundamentals and web scripting, and second-year students in web application development. I’ve also taught database, server administration and other fundamental technology essentials.” Brandon teaches in both the Interactive Media Developer Diploma (IMD) program and the Information and Computer Systems Technology Diploma program, and sees students right out of high school, international students, as well as people who are looking for a career change.

After hearing him say how much he loved teaching, I wondered what it was about it that Brandon enjoyed most. “I love seeing new students eager to be here on the first day and the energy that entails, then moving them from that initial energy and excitement to two years later when they’ve proudly completed a project for industry, and knowing you had a part of that journey. Then there are those in-the-moment connections you make with the students when you see those aha moments.”

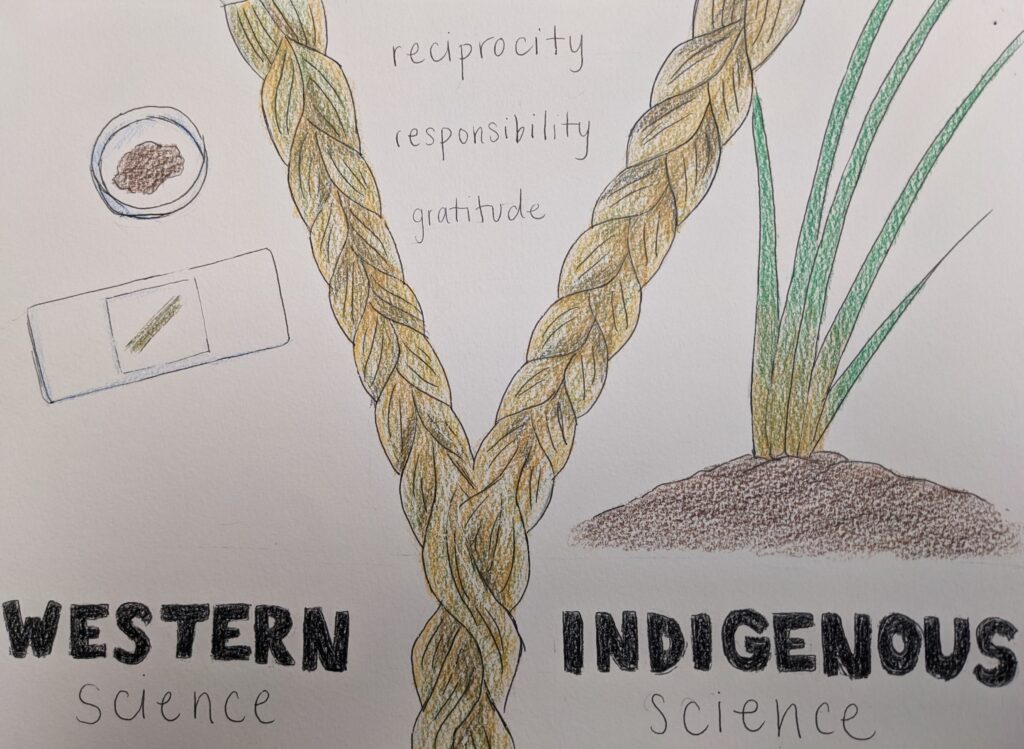

Last summer, Brandon participated in the Working Together: Indigenizing Your Course program with Natasha Parrish and Charlotte Sheldrake. “I’ve been curious adopting a more holistic approach in my teaching mainly because of my IMD students who tend to be open and curious. During the program, I chose the Circle of Courage as my Indigenization framework. That framework has the student move through four phases of a journey, starting from belonging and mastery and moving through independence and generosity.” You may wonder how that meshes with creating programs and web pages, and Brandon explained. “At the beginning of their lab block, students think about what they’ve been learning throughout the week, engage in self-reflection, and ask and answer questions in small groups, like a sharing circle, but asking questions based upon content mastery or working towards independence, as well as sharing how their week has gone in terms of their course work. And through that process of sharing, students learn from each other. I’ve had more than one student comment that this was the best part of the course because they heard other perspectives, which helped them when they were struggling. Other students were grateful because they thought they were alone in their thinking but now realized that other students were feeling the same way.”

I wondered which courses Brandon had Indigenized using this framework. “My plan was to do it just with the second-year courses, because I had already built trust with those students in earlier courses. But I thought, maybe I could try it with the first-year courses as well. And it turns out that those first-year students were just as game to give it a try as the second years.” And while the second-year group was already cohesive, Brandon has found that the first-year students he worked with last term have become even more cohesive than that second-year group. And this winter term, Brandon is integrating this framework in all his courses. What he has learned is that “you don’t need to work with a group you have already built trust with. You just need to be confident and detail the reason behind the framework, and now I have seen the positive impacts of making space for students to ask questions course concepts, and how what they’re learning contributes to the entire group becoming stronger together.”

I wondered how Brandon integrated this framework worked in his classrooms. “It’s impossible to rearrange our computer labs to create a circle. So, I ask everybody to stand and the people in the center to move around to the outside edges. Then for ten-minutes we move counterclockwise, everybody taking their turn and listening. For the bigger questions, we break into smaller groups, and I ask them to sit in circles with their computer chairs as best we can.” But Brandon wanted to also mention that his students still complete all their labs in lab time. “We still get everything done, but our time in circle means they’re having a better time of it and are more connected. And I, myself, was energized right through to week 13 of the course.”

I asked if Brandon had shared his experiences with his fellow faculty members. “I have talked with my colleagues about how I’ve Indigenized my courses – it’s not been a huge leap for me so I’m sharing enthusiastically with them. Whether any of them will try something like this, I don’t know. I’m a relatively new instructor and am taking the Provincial Instructor Diploma Program, so I’m in learning mode, but I can appreciate that everyone has their own tried and true methods of teaching.”

In addition to Indigenizing his courses, Brandon has also been working with Ungrading. “A faculty member in our department, Melissa Mills, had been working with Ungrading in her course and last summer, I borrowed her book on it to learn more. At first, I was not impressed, but before I finished the first chapter, I knew how I could implement Ungrading in my courses.” Because many students in Brandon’s program experience a lot of anxiety these days, he wondered if taking away grades would alleviate some of that anxiety. “As I read the examples in the book, I realized that Ungrading is not about awarding students with a letter grade. Rather, it’s about supporting students to gain a better understanding of their own capabilities which will then help them succeed in industry.”

When Brandon returned to work in August, he worked to move one of his courses to an Ungraded model. “In my labs, I already worked students to mastery. While there are marks assigned, students all have the opportunity to get ten out of ten. For example, if there’s something wrong with their submission, I would ask questions to probe their comprehension, give them feedback, and they resubmit their work based on that feedback.” But then Brandon added a self-assessment component to the guided part of the course. “At week five and week ten, I sat down with each student to ask a series of questions to get them to think about their work in the course, including: Where do you feel you are for comprehension? What sort of grade would you give yourself so far? How much time are you dedicating towards study and labs? Where are you feeling weak and where are you feeling strong? Was everybody accurate? No. In fact, the majority of the class underestimated their abilities.” Brandon likened his course to learning how to drive, where this part of the course represented reading the driving manual and taking the knowledge test. But you still have to do the road test, which in his course is the final exam. By checking in with students at weeks five and ten, Brandon could help them see how prepared they would be for that road test. “I also asked them to self-assess their work on the final exam, but I would also assess them and compared my assessment with theirs and most students assessed themselves within 3-4% of my assessment, and if someone was way off base, we would have a conversation about that and suggest ways for them to move forward.”

Brandon cautioned that while many people think that Ungrading is less work than traditional assessment, “that one-on-one mentorship for the labs and the final exam is the same amount if not more work. But, while giving that feedback and thoughtfully moving each student to their next step may be more work, the payoffs are that the students have a better understanding of where they sit as far as proficiency. I will also say that the grades given under Ungrading were much more accurate than they were when I used a simple rubric without considering comprehension. I also found that students appreciated the fact that it wasn’t about me taking points away from them which could result in wearing down their motivation, but rather about giving them the opportunity to improve and work towards mastery.” And that working to mastery is something Brandon working to integrate in all his courses now.

For the most part, student reactions were positive, but some students can be uneasy because they have never experienced anything like Ungrading before. For those students, while Brandon encourages them to try, he says “if being Ungraded adds additional stress, I will grade students in the traditional sense, if that’s what they need. In the end, we’re here to help the students complete their programs, but if we can build in additional skills like critical self reflection, wouldn’t that be great for industry? Or building better human skills in the case of the Indigenous learning framework. Can you imagine building that into a workplace?” Our programs don’t have to be only about their topics and content.

More instructors in Brandon’s department are considering Ungrading for assessments, perhaps partly as a reaction to GenAI. He says, “I would argue that it is much harder for students using GenAI tools to succeed in an Ungraded course than a traditionally graded course, because those tools prevent students from gaining the foundational skills necessary to complete the assignments, and if we require those students to critically self-reflect on their comprehension, they will struggle to answer the questions we ask.”

I asked Brandon what advice he might have for faculty wanting to Indigenize their courses or integrate Ungrading. “You don’t have to get it right the first time. Indigenization will lead to a more fulfilling, enriched experience for you and your students, because of the connections it makes and the lightbulb moments you see from the students. Try something small like guided labs or just 5 minutes at the beginning of a lab to sit and ask students about their experience because they are going through that experience together and building community together can result in a better environment, and hopefully a better outcome for the course. It’s okay to be brave and try new things, even with baby steps.”

As we came to the end of our conversation, Brandon added some final words. “I’m grateful I was able to explore Indigenization and Ungrading for my courses, and for the supportive faculty within the college who have been a sounding board for my ideas.” And while some people might think that technology programs are not the best fit for Indigenization, it’s even more important to bring out human aspect in courses like these, where the humanity is often hidden. “In the end, adding these human approaches into our teaching, can make classroom experience much more rewarding.”