Today we have a story of STEM Accessibility. What is STEM Accessibility, you may ask? Well, to give you an example, what happens if you’re teaching an online math class and want students to look at a formula, but they are unable to see it and have to rely on a screen reader to access the information? Sounds simple enough, and it would be if it were a sentence in English, but for mathematical formulas, it’s not that simple. So, I wanted to talk to Chris Avis, Kristina Andrew, and Sue Doner about a recent project they worked on to create more accessibility in STEM courses, to see what they found was possible and what work still needs to be done. But first I asked each of them to tell me a bit about themselves and how they came to this project. (Note that this work received an Accessibility Recognition Certificate in 2024)

Chris has been a faculty member in the School of Arts and Sciences for 15 years, primarily teaching physics courses. “First-year students often take our courses. But when physics is not their preferred discipline, they sometimes have a hard time with the course material, so I try to do whatever I can to make things easier for them. During COVID, I began looking at the resources we were creating for online learning and wondering how we could make those resources accessible, not just to those students who have identified accommodation needs, but for any student who may have to miss class due to life getting in the way.” Chris admitted to being both intrigued and intimidated by making physics resources accessible. “It’s a lot of work to get even one lecture designed for accessibility because physics is highly visual and mathematical, with a lot of text, jargon, equations, graphs, sketches, etc. So, finding ways to present content so that it is accessible without creating a massive workload issue is a challenge.”

Kristina has been at the college for 20 plus years, working primarily as an instructional assistant with students which is where she first began learning about accessibility. “When I was in lab with students working on statistics, we had a couple of students who had difficulties seeing information on the computer screen. I was shocked by how much effort it was for the student to access the material – they had to zoom in on one single number to see it, then zoom out and zoom in again on the next number, and so on. Whereas, had the material been accessible, the student could have just listened to it.” More recently, Kristina has been a term instructor in the Psychology Department as well as an instructional designer in eLearning where one of her roles is supporting faculty to make their courses more accessible for students. “While doing this work, I have heard from faculty in engineering, math, physics, about the barriers to creating accessible course materials, and how they have found that students will self-select out of those programs when materials are not accessible.”

Sue has been at the college for 11 years and involved in online education for over 20. “My interest in web accessibility was lit 20 years ago, when I attended a conference and discovered that the bespoke websites that I’d been proudly building were pretty much unintelligible for anybody who was blind. But I learned that you can make websites accessible to someone who is blind, which was an amazing gift.” Sue notes, however, that her background is in English and history, not math, so making equations, etc. accessible was still a challenge. “I went to a conference several years ago, where even folks who speak math and programming couldn’t agree on which markup language was best to use to represent equations allowing students to access them using assistive technologies. It is so much easier to make text and images accessible digitally than any equation in math. So, I needed to work with people who speak the language of equations to help me understand what an equation should sound like through a screen reader, as well as what markup languages would work best for different equations.” Her own challenges helped Sue understand the challenges faculty, who may not be comfortable with digital tools, might face trying to create accessible materials for STEM courses. “We can’t have the same expectations of STEM faculty creating accessible materials as we might of faculty teaching art, history, English, or business courses. This is a niche area that requires more competencies and more support to develop those competencies.”

And this is where, Sue said, the three of them came together. “Kristina and Chris already worked well together, and my role was initiating the project, working with Kristina on the D2L templates, and working on the question if we’re trying to promote accessibility for other people teaching in these disciplines, how do we create a process that people could adopt and adapt without it being a crushing burden?”

The project scene set, I asked Chris to talk about the problem he encountered and his connection to CETL. “Kris and I have talked a bit about some of these pieces, and I knew that Kris had also been working with Stephanie Ingraham in our department on an e-book for one of the radiography courses. We started by looking at the WORD templates Stephanie was building to see how they were working. But the challenge I was most concerned with was understanding how instructors use equations and the limits of text to speech technology in terms of capturing how they’re being used in the classroom.”

![]()

“Take this simple equation y equals mx plus b. When we work with students in the classroom, we have to take them from reading those letters literally to understanding what that equation means. What this equation tells you is that there are two things you are measuring: there’s a variable that you plot on the y axis, and there’s a variable that you plot on the x axis. The letter “m” is a number called the slope, and the letter “b” is a number called the y-intercept. So, while text-to-speech software would read this equation as “y equals mx plus b,” really what we’re saying it that one variable is slope times another variable plus y intercept.” And, of course, most equations in Chris’ physics class are much more complicated than this. “They are not only challenging to typeset but doubly challenging to get text to speech software to read them properly.”

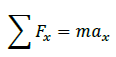

What you would get if a screen reader were to try to read this first line, is something like Sigma F subscript X equals M A X subscript. But what this equation tells us is that we’re going to add up all of these pieces of forces, and that is equal to mass times acceleration. So, when I discuss this equation in class, I don’t say Sigma F x equals M A X, I say sum of forces equals mass times acceleration. So, we knew that it would not only be challenging for the existing technology to read the equation coherently, we would still be missing what the equation is meant to communicate. To emulate the in-class experience, we would need to translate these equations verbally, not just have them read out by a screen reader as you would for English materials.” So, they decided they would need to provide multiple modes of access for students, meaning “typed notes for people who had no eyesight problems, and videos or audio notes where you could engage with the equations in a way that that would make sense of what you’re trying to communicate.”

Kristina jumped in here to speak to some of the complexities she and Chris began to uncover. “We were also catching anomalies, for example the letter “m” can mean mass, or meters, or minutes so Sue and I reached out to ReadSpeaker and discovered that their development team had already identified scientific terms and jargon as a limitation in the tool and were compiling a database so it could begin to interpret these terms accurately, which the developers admitted would be a long project.”

But, Chris, Kristina, and Sue wondered, what could they do for students now? “I started contacting faculty across the college, in engineering, physics, math, and chemistry, to find out what they were doing in classes that was working (which we could share with other faculty), but also that wasn’t working and where there might be gaps. Out of those conversations a few things happened. Larry Lee in chemistry found a publisher resource that he’s now piloting to help with the atomic structures. And the three of us discussed ways faculty could present information to students. For example, if they were recording a video, rather than saying here when referring to an equation, they should talk about the equation they are describing. However, this created more questions than answers and we still have a long way to go.” In addition to talking to people at Camosun, Kristina explored what other institutions were doing. And what she discovered was not a surprise: “this takes time, a lot of work, and training to learn the technology, and there are no resources we can point people to because they have not been created yet.”

Chris then spoke to challenges beyond the classroom, namely college structures. “It is very hard for a single faculty member to create accessible resources, both in terms of time and skills, and we may need to explore a model where faculty are primarily delivering course materials, but instructional designers are primarily developing those materials. Sharing resources also becomes important, and with multiple sections of one course, the expectation should be that these resources are all shared within a department, including with new term faculty, rather than having five faculty members developing five separate sets of resources on top of an already backbreaking workload.” And the ultimate goal, Chris believes, is for post-secondary institutions across B.C. (and beyond) to share the resources they create, especially since science course curriculum is fairly standard across institutions.

Kristina also added that they brought in the Centre for Accessible Learning to find out more about what assistive technology tools were being used to support students taking STEM courses. “There are some tools that can support math accessibility, or that can take images of handwritten documents and digitize them using Optical Character Recognition (ORC) (with the help of AI), but there are financial and digital literacy barriers for faculty and students who don’t know how to use these tools, meaning someone needs to provide support – both in terms of money and expertise.” But if faculty and departments work together, then it’s not on one person’s shoulders to make a course accessible. “And if those resources are shared with people in other departments, they can build off of that work where the content overlaps.”

Chris, Sue, and Kristina all reiterated that creating accessible course resources is a workload issue for faculty, one that is not easily definable given that there are no guidelines at the college around how accessible course materials need to be. Chris reiterated, “if this is to become a college priority, we have to properly resource people to do the work; it can not be done off the side of people’s desks. We need to find a way to articulate how much time it takes to create or revise one module or lesson so that it is accessible for at least 80% of students, and also so that it is accessible for every student. We could be looking at ten plus hours of work just for one lecture and there has to be recognition of the resourcing required to do that, and a desire to invest in that.”

Which of course led us to Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Kristina pointed out that “while there might be one student in a class of 40 with low vision, that doesn’t mean that adaptation of the materials would be just for that one student. This is bigger than one student, and students may not realize how much they benefit from accessible content until they are using it. How many students in a math class would appreciate an equation being read to them in a way that’s not symbolic? We won’t know until the instructor has the tools, the resources, and the support to be able to convert their content into a more accessible format.”

Sue built off of this by saying, “we started with digital accessibility of STEM equations, an impossible goal. But the project and the approach nestled more into a Universal Design for Learning mission because Chris has created materials using multiple modes of representation, including videos to describe things, described images, breakdown in text format, using HTML templates, etc. and throughout, he has been both making his content inclusive and accessible, and discovering all the work a faculty member has to do to make this happen.” And Chris added that we need to engage in discussions with our unions and administration as to how we can support ALL faculty to do this work, even faculty who have Scheduled Development time, because they may need to use SD time for other work. “If our vision is to make accessibility a priority, how do we work together to be fair to all union members, and to encourage and fund this kind of work so that we’re making life better not just for students, but for all the faculty as well? If we released a faculty member for a term or a year so they could focus on making the most accessible course possible, then they reported out on how it worked for them, that would pay dividends over time. I hope there is an investment in this kind of research and development at the college because I think it will have profound implications for workload and sustainability for projects like these going forward.” And as Sue pointed out, “now that we have provincial accessibility legislation and expectations on post secondary institutions, wouldn’t we want to be proactive by having someone fully released to help us move towards those expectations as opposed to reacting in a panic later?”

I wanted to bring the conversation back to something that had been mentioned earlier in our conversation: D2L templates for creating accessible content. Kristina started us off but saying “When I worked with Stephanie, I discovered that many of the documents she was providing to students were PDFs. So, we talked about the barriers PDFs present because they aren’t typically formatted in an accessible way. We explored WORD documents as well but discovered that the WORD extension that supports equation writing wasn’t doing what we thought that it should be doing: the equations looked better, but they were not being translated from text to speech accurately.” After exploring a variety of options, the team landed on HTML as providing the most accessible format, albeit the most labour-intensive for faculty to learn to use. But choosing a solution that would not work for faculty, was not a feasible solution, which was where the templates came in – creating as much digital accessibility as possible while recognizing that the STEM piece of it was still a work in progress. But also sharing the HTML templates across departments so faculty don’t have to reinvent them all the time.

I wondered what was next in this project, and Kristina said using Generative AI! “A faculty member and I worked with handwritten material, because one of the things that’s unique with STEM is that information is usually presented step by step, with faculty writing out equations or solutions as they unfold. We took a picture of the material, fed it into Generative AI and asked it to spell out each of the steps of the equation. And it did a pretty adequate job, at least to the point to allow a faculty member to describe what is going on without having to spend 2 hours explaining each step.”

Chris also had a great idea to make this work more manageable. “You could have a project for students, perhaps in lieu of doing a lab report, where they could take a piece of material from the course and experiment with tools they are already using, to make that material accessible, then have them critique the results for accuracy. You could then feed that material back into the class, in that circle of courage idea of generosity and mastery – students create a resource their classmates (present and future) will benefit from, develop their proficiency in using GenAI in a good way, and work together to assess the reliability of their work.”

In terms of how to bring accessible course design to the attention of people at the college who might not know about it, Chris says, from his experience on curriculum committees, “when curriculum is brought forward for review, they have to have an Indigenization statement and an applied learning statement, but I think there needs to be an accessibility statement as well. I’m hesitant to add more to the curriculum development process itself, but these three priorities could run in parallel.” And in addition, Chris notes, wouldn’t it be an amazing opportunity for Camosun to lead collaboration with other post-secondary institutions given the budgetary crises we are all facing right now.

As we came to the end of our time together, I asked Chris, Kristina, and Sue what final words they had for me. For Chris, this project has pointed at cracks in our foundation as an institution. “I think a big part of the problem is that, even pre COVID, faculty didn’t have the bandwidth to make significant changes to their course materials. The culture of the institution needs to be in the right place around sharing and realigning what we should be doing as faculty, instead of everyone trying to do everything all at once and having no time to do anything. So, I hope there’s an empowering way for us to take down some of those silos a little bit, recognize that we’re all on the same team, and realize that we need to do things differently. I don’t know how to have that discussion, but I do feel like a time of crisis sometimes highlights why we need to do it because we cannot keep doing what we’re doing without burning out.”

Kristina wanted to thank all the faculty members who answered her call for help. “I reached out to people during SD and vacation, Pat Wrean, Susan Chen, Stephanie Ingraham, John Lee, Benji Birch – not one person turned me down which I think highlights the special faculty that we have at Camosun, who are committed to creating environments in which everybody feels welcome and doing anything they can to support the students at the college.”

And for Sue, “there is no ‘we’ll just do this and take care of that’ when we talk about creating more flexible opportunities for students. Because if you want to create more opportunities for STEM programs, these are just some of the barriers and challenges that will just become bigger if we don’t begin to address them now.”